A C++ mocking framework is supposed to make unit testing easier, but in real C++ systems, it often becomes harder: static calls, non-virtual methods, third-party binaries, and code you can’t safely refactor. Typemock Isolator++ is a C++ mocking framework built for that reality, enabling isolation at runtime so you can test legacy code without changing production code.

In this part of the Typemock Architecture series, we’ll explain, at a high level, how Isolator++ makes mocking the unmockable possible in C++ and why the v5 engine is built for modern CI, Linux, and real-world codebases.

What makes C++ mocking fundamentally hard

Most C++ mocking tools assume you designed for testability (interfaces everywhere, dependency injection, wrappers, link-time tricks). But production C++ rarely looks like that:

- Global/static functions with side effects

- Third-party libraries you can’t change

- Legacy code with tight coupling

- Complex call stacks and exceptions

- Multi-threaded test runs in CI

So the core question becomes:

How do you isolate behavior without rewriting production code?

The Isolator++ approach: intercept at runtime

Isolator++ doesn’t depend on “nice architecture.” It operates at runtime, at the level where the compiled code actually runs.

That means:

- No forced interfaces

- No source rewriting

- No “just refactor it” requirement

- The interception is active only during test execution

✅ Typemock is built for teams shipping real C++ code, not textbook examples.

How the Typemock C++ mocking framework works at runtime

Test runner starts the test process

- Isolator++ loads into the test process

- A configured call is intercepted

- The engine chooses: Return, DoInstead, or CallOriginal

- Test finishes and the process exits (no persistent hooks)

Nothing is modified on disk.

Nothing remains after the test process exits.

Why “just refactor it” often isn’t realistic in C/C++

When someone says “Just remove statics” or “Make it virtual so you can mock it”, they’re assuming you own the design and can safely change it. In real systems, that’s often false, and in C++ it can be painfully expensive or dangerous.

1) ABI and binary compatibility

Turning a non-virtual method into a virtual one can change the object layout (vtable pointer, layout/order of members), which can break:

- binary compatibility across DLLs/shared libraries

- plugins loaded at runtime

- third-party components compiled against older headers

Even “small” changes can trigger crashes that only appear in production configurations.

2) You don’t control the code

A huge chunk of static/non-virtual calls come from:

- third-party libraries

- legacy internal libraries used by multiple products

- OS APIs / vendor SDKs

You can’t refactor them, and wrapping them everywhere is time-consuming and brittle.

3) Wide blast radius (static calls are everywhere)

Static calls often end up scattered across the codebase:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

// spread across hundreds of call sites auto path = Config::GetInstallPath(); Logger::Write("start"); auto h = File::Open(path); |

Refactoring this to DI means touching many files, changing many constructors, and creating a long migration period where everything is half-old / half-new.

4) Inlining, headers, and templates amplify the pain

In C++, many non-virtual functions are:

- inline in headers

- template-based

- compiled into multiple translation units

Refactoring becomes a full rebuild, linker debugging, and performance risk, not a small change.

5) Behavioral risk: statics often hide state

Statics may include:

- caches

- singletons

- global configuration

- lazy initialization

- hidden threading constraints

Changing them can introduce subtle race conditions or initialization-order bugs.

6) Performance and determinism requirements

Some systems avoid virtual dispatch intentionally:

- Low-latency trading

- Realtime or embedded systems

- Allocation-free or deterministic code paths

Adding abstraction layers (interfaces, heap-injected dependencies) can violate performance budgets or memory constraints.

Before and after: what refactoring really looks like

Before (typical legacy)

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

int PaymentService::Charge(int userId) { auto token = Config::GetToken(); // static auto ok = Gateway::Charge(token); // non-virtual/3rd-party Logger::Write(ok ? "OK" : "FAIL"); // static/global return ok ? 0 : 1; } |

The refactor you’re being asked to do

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

struct IConfig { virtual std::string GetToken() = 0; }; struct IGateway { virtual bool Charge(const std::string&) = 0; }; struct ILogger { virtual void Write(const std::string&) = 0; }; class PaymentService { public: PaymentService(IConfig& c, IGateway& g, ILogger& l) : cfg(c), gw(g), log(l) {} int Charge(int userId) { auto token = cfg.GetToken(); auto ok = gw.Charge(token); log.Write(ok ? "OK" : "FAIL"); return ok ? 0 : 1; } private: IConfig& cfg; IGateway& gw; ILogger& log; }; |

This is “clean” – but it’s also a lot of change, and sometimes it breaks ABI, performance, or release timelines.

What Typemock enables because of this reality

This is exactly why Typemock Isolator++ exists:

✅ You can unit test now, even when the code is not refactor-friendly.

✅ You can isolate static/global/non-virtual behavior without redesigning your system first.

✅ You can refactor later when it’s safe, not because a testing tool forced you into it.

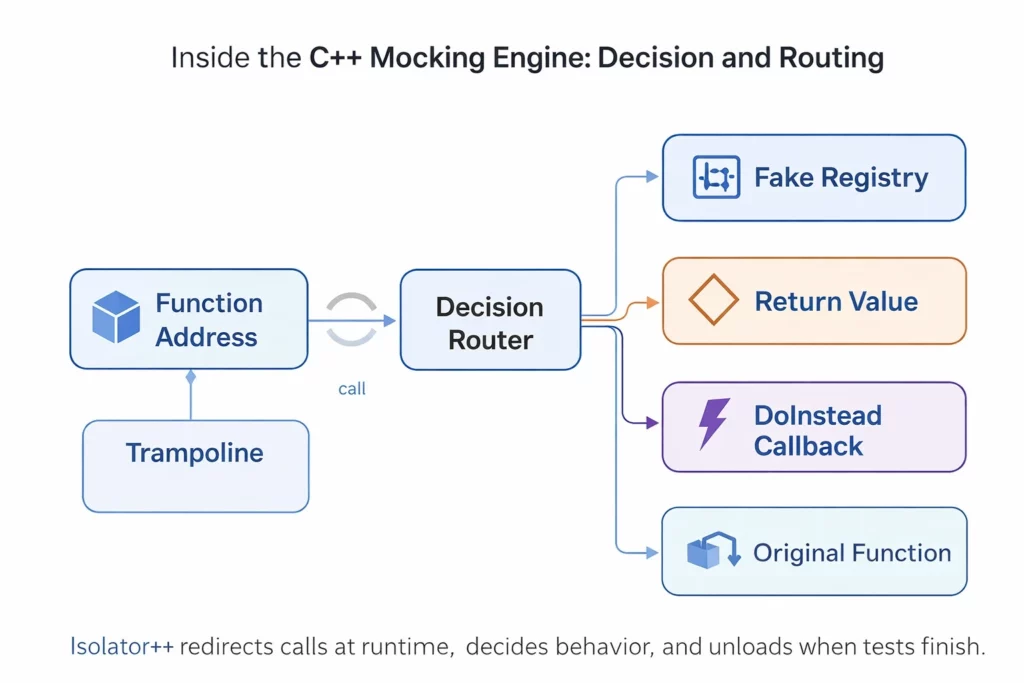

The trampoline engine (high-level)

At the heart of Isolator++ is a “redirect and decide” mechanism often described as a trampoline:

- Execution reaches a function you want to fake

- The engine redirects control to a safe handler

- The handler decides what to do

- Execution returns to the test (or to the original function)

This design is what enables:

- Mocking global/static/free functions

- Intercepting calls across module boundaries

- Handling hard-to-test dependencies without rewriting

Why v5 matters: Windown, Linux, GCC and safer unwinding

Modern C++ teams run CI on Linux, across compilers, with lots of parallelism. Isolator++ v5 is designed for that environment:

- Windows Support (VS 15 and above)

- Linux support (GCC 5.4 and above)

- Modern API (C++14 baseline)

C++ mocking framework examples: from unmockable to mockable

Example 1: Mocking a static method

Production code (unchanged):

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

int PaymentService::Charge(int userId) { auto token = Config::GetToken(); // static return Gateway::Charge(token); // non-virtual / third-party } |

Test using Isolator++:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

TEST(PaymentServiceTests, Charge_Succeeds) { auto a = Isolate(); a.CallTo(Config::GetToken()).WillReturnFake(); a.CallTo(Gateway::Charge(A::Any()).WillReturn(10); PaymentService svc; bool result = svc.Charge(42); ASSERT_EQ(10, result); } |

No interfaces.

No wrappers.

No refactor required.

Example 2: Mocking a global / free function

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

bool SendPacket(const char* payload); TEST(NetworkTests, PacketFailureHandled) { auto a = Isolate(); a.CallTo(SendPacket(A:Any())).WillReturn(false); auto ok = ProcessNetwork(); ASSERT_FALSE(ok); } |

This works even if SendPacket lives in another library or is locally copied.

Example 3: Replacing behavior with WillDoInstead

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

a.CallTo(SendPacket(nullptr)). .WillDoInstead([](const char* payload) { return strlen(payload) < 1024; }); |

This is extremely powerful for:

- simulating failures

- edge cases

- complex behaviors

- time-dependent or flaky dependencies

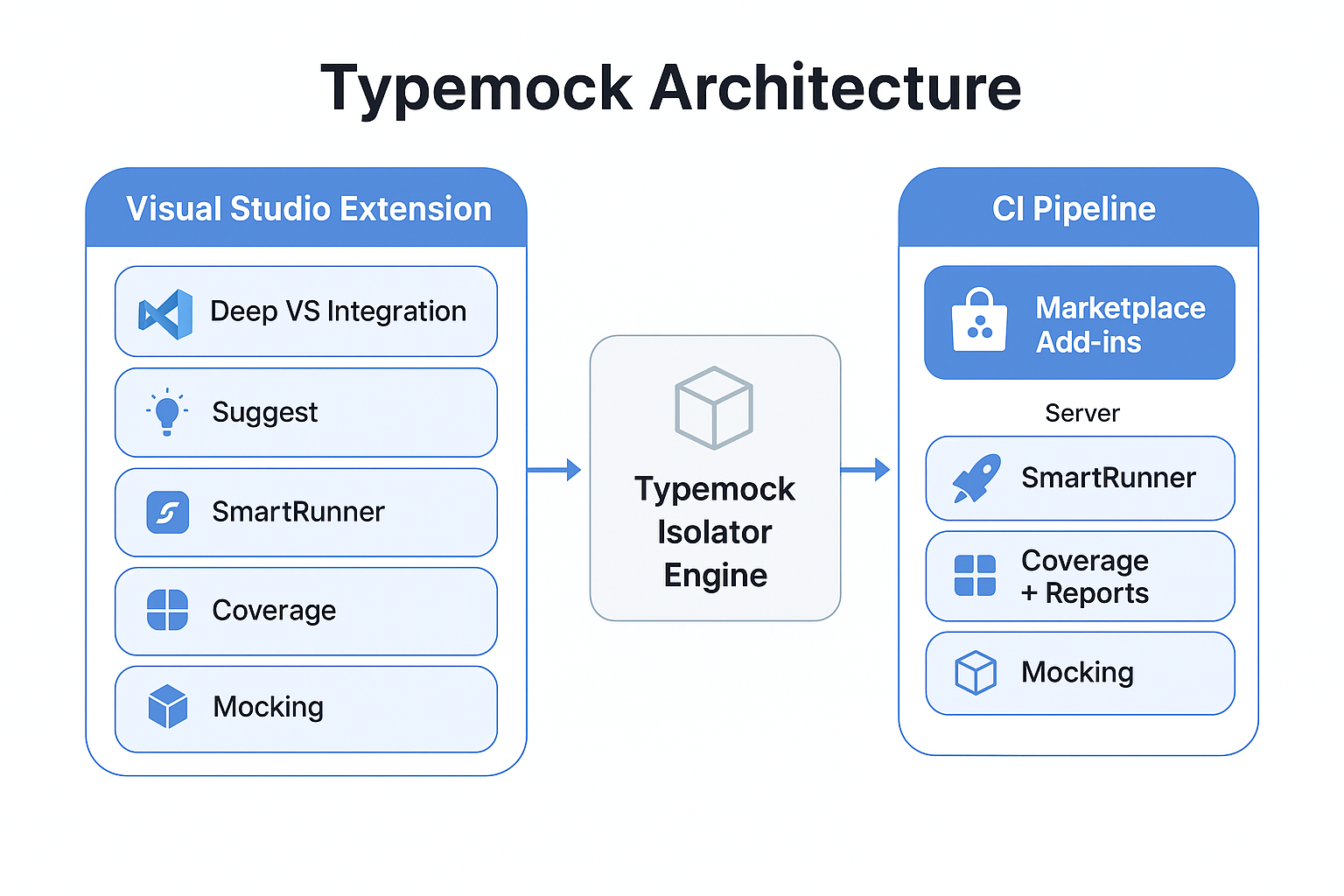

Where this fits in the full Typemock architecture

Isolator++ is one layer in the broader Typemock system:

- Mocking / Isolation engine (this post)

- SmartRunner (impact-based test running)

- Coverage (instant coverage + reporting)

- Deep IDE integration (especially Visual Studio)

This is what allows a team to go from “we can’t unit test this” to “tests run fast, in isolation, continuously.”

Test frameworks commonly used with a C++ mocking framework

Most teams using a C++ mocking framework like Typemock run their tests through standard, well-known test runners:

- GoogleTest (gtest) — a widely used C++ unit testing framework for writing and running tests.

https://github.com/google/googletest - CTest — CMake’s test driver, commonly used in CI pipelines to execute C++ test suites.

https://cmake.org/cmake/help/latest/manual/ctest.1.html - Microsoft Test Platform (VSTest / MSTest) — the test platform used by Visual Studio and Azure DevOps pipelines, commonly running native C++ tests on Windows.

https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/dotnet/core/testing/

Typemock Isolator++ works with all of these runners, loading only inside the test process and acting as a C++ mocking framework at runtime without requiring changes to production code.

Next in the series

Part 4: coming soon (what changes the economics of unit testing).

Part 1: How the .NET Isolation Engine works

Part 2: Inside the .NET Isolator Engine

Download: Isolator++ (C++ mocking framework trial)